SISIFOS

ART AS A THERAPEUTIC TOOL

SITE SPECIFIC INSTALLATION

CREATED FOR THE PUBLIC SPACE

AN INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH PROJECT

Introduction

SIDE Project / Eugenia Tzirtzilaki

In the context of the action, a parallel procedure was developed in connection with the physical presence of the art work in the places where it happened. Eugenia Tzirtzilaki listened on people and areas.

She developed a deep dialectic research of the past and the present. Her interaction with the event of the exhibition, led to the event of the interaction with the physiognomy of the space and the inhabitants, as an additional connecting tool.

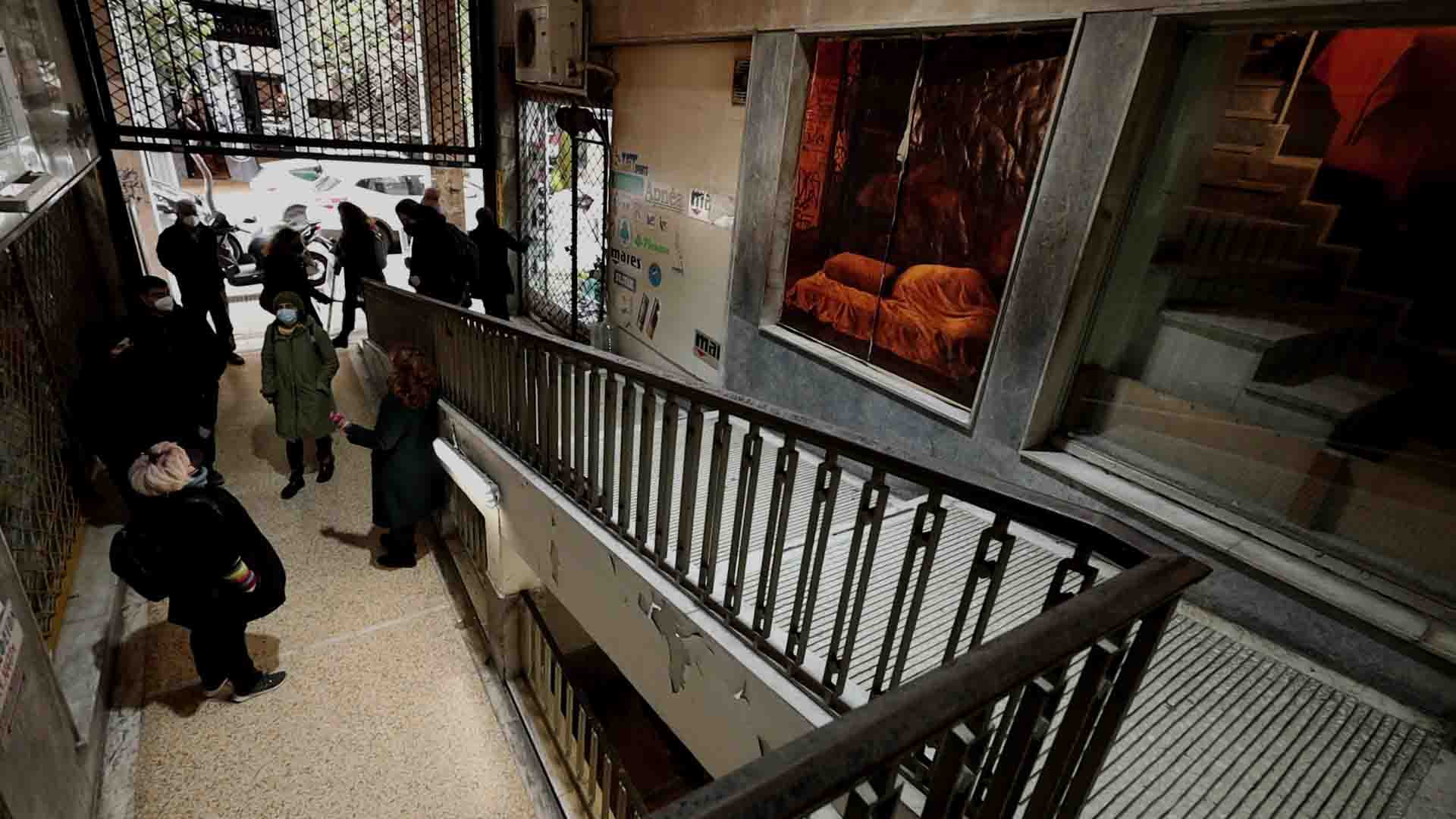

As a result of this process, the “Emotional sightseeing” was developed and implemented in the areas of Stoa Anatolis. It is a dramatic composition of speech, narrative, and site specific theatrical action, which implemented for a limited number of viewers in March 2022.

The guests followed a prescribed walking route with inspirer and

guide – interlocutor herself. This route composed, parts of history elements of the building complex, inhabitants personal documentary stories, oral testimonials, as well free partial involvement of the residents during

this action. The following texts are part of this parallel path.

The: “Feet and Eyes”, concerns on the complex of buildings

on Aeschylus Street. The: “Hands and Ears” concerns on Stoa Anatoli.

Based on what is described, the site specific parallel action entitled “Emotional Sightseeing” was implemented.

[ Legs and Eyes ]

Everything flows, cities are constantly being transformed, but right now Athens is changing in an overwhelming way. The small-scale gentrification experiments that we watched unfold during the past decade in run-down neighborhoods where poor families were expelled from their homes for the aesthetics of the bourgeoisie to nest, are now normalized. And if there isn’t enough local customers for all the lofts and fine restaurants, it doesn’t matter. Tourists and digital nomads are a willing audience with their purchasing power.

Many investors have started renovating and reshaping not only houses and apartments but also city landmarks, such as emblematic buildings, galleries and patios in the center. At the same time, the Great Walk (Megalos Peripatos) remains an enigmatic vision that will change the face of the city but no one knows exactly how, while other public spaces such as small and large parks, groves and green hills in various parts of Athens have been fenced and locked in the midst of the pandemic, minimizing citizen access to them.

What you dramatically need shrinks just when you need it the most. Does this increase its value? When control is exercised over the necessary, it makes invaluable. What is the value of a thing, when it can no longer be measured?

For some of these spaces occasional calls appear for an organized response to the intention of handing them over to private managements, although it is difficult to follow the thread of these struggles, the history of the opposition for each of these places and their current course. There are no calls for participation in public consultation that would stir the citizens’ imagination and listen to their needs, but even information about upcoming or current changes in the city usually don’t find a spot in newspapers and television broadcasts. So one has to either stay in some sort of digital room with others who also wonder more or less about the same things, sharing information like secrets that have miraculously crossed enemy lines, or remain a mostly physical observer of the space that changes around him.

As the ground is literally cut under our feet, we are seeing it yet we don’t not always understand it. As if inside a mute dream, we are only feet, legs, legs and eyes, which occasionally arrive at places they know well but find there nothing familiar. Am I in the wrong place or is it that what I’m looking for only exist in the past?

Even when not in lock-down, with restaurants open and a vaccination certificate in my pocket, during the Covid years I walked around the city more than ever. I saw the Book’s Gallery (Stoa Vivliou) deserted – I hear it will be filled with restaurants. In my neighborhood, the public garden of Finopoulou hill is locked very night, even though it is winter and an arson (an excuse used by the government for locking parks) is highly unlikely. What strikes me as bizarre is that the middle-aged man who comes to lock the gate drives the car of a private security company. What has happened? Who should I ask?

The gallery on Aristeidou Street has lived many lives; some people there open their small warehouses for us and cry as they talk about the passion and stubbornness these spaces have hosted. They cry because they have no one to pass this story on and that makes them feel transparent too, they cry because they hear that investors have an eye on the gallery and they might be evicted in the near future, they cry because a store that closes down is not replaced by another, but rather by an anonymous mega-company that devours all the closed stores together and spits out cheap labor, i.e. people who simply lost everything when they entered the quarantine-era right after a decade of crisis.

The small gallery on Fidiou Street has already been sold in its entirety and is waiting to be transformed into some kind of hotel facility. Sami, who lives upstairs and has filled his doorstep with flower pots, stands next to them describing the jazz rehearsals across the street, years ago, when he would stay up with a beer just to listen to them – these guys have all gone to America now, or the Netherlands, somewhere, having a career. He describes his daughter’s visits there in the gallery, his adoration for her and what he fed her in the mouth inside this small room with a door that doesn’t close, he talks about other neighbors over the years, the electrician, the stationery store. Wherever he rests his eyes a memory appears. Each corner and side of the gallery is a three-dimensional palimpsest loaded with relationships, sensations, feelings.

Everything flows, cities are constantly being transformed, indeed, but the body, the human body that consists only of meat and memories and nothing else, needs traces: to be able to find them and to leave them behind.

Where do the stories of collective ventures, of surprising coexistences, of multicultural mosaics and diversity go, when a space is emptied, renovated and completely changes use? What becomes of all these stories? How can an Athenian alley be distinguished later from a one in Hong Kong or Seville? How does a place become a non-place and how does one resist the razing brought about by the rapid transformation of a city after its inhabitants’ impoverishment, the fast and cheap selling of houses and shops, the assignment of more and more areas of public life to private companies? The city, apart from matter and real estate with rising and dropping value, is also a carrier of memory. The immaterial, metaphorical, symbolic and emotional space that is available for this memory, the respect for it, the recognition of its right to exist is deeply healing.

It is healing to be asked and to have the space to speak.

Other than my participation in the stage of conceptual development, my contribution to the SISIFOS project has two parts. We started by posting in the Aristides Gallery a poster that we made together with Maria Karathanou and Angelos Christofilopoulos. Wanting to not make something for the people in the gallery (tenants, owners, residents, users, passers-by, visitors), but something with them, we posed the following questions.

Do you remember the first time you entered the gallery?

What is your favorite spot in the gallery?

If the gallery was a song, what would it be?

If the gallery was no more, what would you miss about it?

An anthology of the texts that will emerge from the answers to these questions will be presented in the coming weeks in the form of an Emotional Tour to the Aristides Gallery. This walking performance will serve as a bearer of oral history, a bottle in the sea of time and a message to the future of ways of Being Together that we may need to recall. From pilgrimages to wellness hikes and political marches, moving in space has a healing effect. Since the beginning of time, people have been walking together, telling stories.

But stasis has its own therapeutic value too. Sometimes you just have to stop in order to be able to function. In the first performance the bodies that cross the gallery follow the paths suggested by its architecture, but the second one takes place in immobility. Like the negative of a photo, the second performance shares the same stories, in quiet stillness. The texts are performed inside a room, against the background of a long touring monoplane in the gallery. This time it is us who are still and it is the space that “moves” around us, in the controlled funnel of a dark theatrical condition.

The relationship between movement and stillness is similar to the relationship between noise and quiet in the city. A resting place where one can stay still functions as a retreat, as a place to repair oneself from all the noise one endures, and vice versa. For every amount of time spent in the hustle and bustle of the world, one needs to spend time, different amount for everyone, in silence. And also, old things heal us from the relentless newness of the world. Anything that bears the marks of use, with obvious the tear and wear from it, grounds us in the present moment and makes us, as those who came later, new.

The stories of the people in the gallery weave a net like that of a spider: an invisible but durable product of habitation that is woven through movement and fruits in stillness. The spider, a creature full of legs and eyes, creates its web as appropriation and protection, as a gesture that claims the gallery and casts a spell made of memories against the fear of suddenly feeling like strangers, everywhere.

[ Hands and ears ] (turns out, most people don’t cry at all)

After our poster (see Part A) was placed at key spots around the gallery, we waited but no one sent the email we were expecting. Instead, the people we met there started talking to us. While the Sisyphus installation was being set up in the gallery of Aristides, I started visiting the place daily and talking to the people I met there. Some were there only in the mornings, others only in the afternoons so I visited the gallery during different hours, also observing how the conditions; humidity, temperature, light and mobility changed dramatically from morning to night.

Many spoke to me over and over again, making sure that I understood what they had to tell me. From the beginning, I explained to everyone what my relationship to the Sisyphus project was, and that I was there because I was interested in their thoughts and memories, the stories that they would share with me so that I could then share them with others in an Emotional Tour. This introduction egged some to recall what they themselves considered memorable in their past. Mrs. Nena, who decided to open up a shop selling handmade bags during the frightening period of the first lockdown, told me about her ancestor, Matrozos, one of the famous heroes of the Greek revolution in 1821, from whom she had inherited a wooden chest with his initials inscribed on it. “But I gave it away,” she told me. “I don’t want old things, they can carry many different kinds of energy, good or bad; that’s something you can’t know.” In a small loft in her store, next to the sewing machine with which she makes the bags, she has placed her grandmother’s old sewing machine, a “Singer” from the 19th century. “And what about the energy of this one?” I ask her. “I must have cleansed this one,” she replies. There are no rules that won’t be re-defined by emotions.

Our relationship to the past becomes a relationship with our own past, and History is composed of our own history.

The ephemeral, fleeting character of a live discussion creates an openness which invites people into a relationship rather than a dry exchange. Mr. Thanasis, the 85-year-old tailor who has been in the gallery’s 8-storey building since 1958, invites me every time I visit him for raki and meze. I sit with him during his lunch break, which he shares with friends and relatives who drop by to see him. “What is your first memory of the gallery?” I ask him. “I remember when they were making the mosaics in the corridors” he says, “and we had to step on wooden boards to let them fully dry.” “Many passed through here”, he says, “even Novas, the former prime minister, had a suit tailored in my small workshop.”

In order to learn the craft back then, one had to become an apprentice to someone who mastered it and that’s what Mr. Thanasis did from a very young age. The first phase of the apprenticeship lasted at least a decade, the first year of which he and other apprentices had their middle finger tied to their palm all day long, so as to learn the correct positioning of the fingers. Only when this gesture was second nature to them, when their middle finger remained bended at all times, did the hand become a tool that could sew a straight seam onto the fabric. “And how about the second phase of the apprenticeship, I ask, “how long did that last? When would the learning process be considered completed?” One of the elderly friends, with whom Mr. Thanasis now shares the space, replies: “Never! I’m still learning.” He also apprenticed for years as a tailor and when he left the shop to do his military service at the age of 18, he already knew how to make a proper suit.

As a soldier in Goudi, he met a lot of celebrities too. He comes out from behind the counter and stands in the middle of the room to show me how Pattakos, one of principals of the Greek military junta of 1967, was inspecting them youngsters, holding a ruler and tying his hands behind his back. I ask if he used to hit them with that ruler. “No, he just liked holding it,” he says. He remembers the King from his army days too, “a nice boy” he says. Age itself, tender then, now mature, appears through his words as a condition of coloring the copies of memory. Everything is bright when you are new in the world, it all gets a bit darker as you are growing up, and all colors available flash when you have spent a really long time living.

Once he completed his service, he had nowhere to go, he didn’t want to go back to his home village in Corfu; he was contemplating migrating to America but was apprehensive so until he could decide what to do he found refuge in the only place he knew well and felt safe in; the gallery. He slept at night hidden between the benches, earning the time he needed to short his life out. Finally, he decided to stay in Athens, he worked, made money, created his own shop in Kolonaki, and years later he closed it; now he is back at the gallery and cuts, sews, irons next to his friend, in the familiar little nest of his youth that once upon a time had been his refuge.

“I wanted to make a nest,” says Mr. George, who serves us tea at the ground floor cafe. After a decade and a half when the small cafe-canteen of the gallery was closed, he reopened it, renovated and decorated it with flowers and birds. The birds are no longer there – some died, others were stolen – and he decided not to get new ones, since “one can get emotionally attached and then get really upset” as he tells me. He came to the gallery after seven years of doing the same job in a museum cafe, one that also had outdoor tables inside an enclosed patio, just like here. Recreating another version of that same shape, a quiet parenthesis in the midst of the city noise, a small eye in the heart of the storm, Mr. George serves coffee, drinks and pies made by his elderly mother. He also takes care of all the plants and flowerpots on the ground floor and knows how to make a coffee that only Mr. Thanasis orders anymore: a “yes and no”.

In the cafe I meet Mr. Thanasi’s young landlord. The man from whom Mr. Thanasis was renting his shop for over half a century died and his nephew inherited the space. “In the beginning he always paid on time, then as the years went by not so much, but he reminds me of my father, I can’t evict him, I know that would kill him,” says the new owner. He explains to me that when they met the other day Mr. Thanasis offered to go get some fabric and make a new suit for him. When the custom-made suit is tailored, maybe like the one he’s made for Costas from the nearby stamp shop who had a fancy wedding to go to, the debt will have been more that paid, maybe even putting the receiving party in debt.

This is a luxury that people who coexist for a long time can enjoy: relationships remain as a frame, but the positioning of people within it are changing. The young man becomes old, the one who was given a thing gives time to someone else, and he who owed yesterday, tomorrow becomes a generous giver.

One of the times I visited Mr. Thanasis, when the discussion turned to the current political state of the country, he told me that he was “right-wing”. As soon as I answered that I was more of a left-wing person, he exclaimed full of fake indignation, clearly smiling under his mustache, “damn, just like my son!”. This immediate reaction, to meet someone of diametrically opposite political convictions and immediately look at them as if they were one’s own child, belongs to a world soaked in a magnificent sense of morality, which I had only heard of. This tenderness, which no one expects of anyone else and no one owes to anyone either, creates a gratitude towards the other person and at the same time opens up a political space inside the small weathered room, where one can speak without fear of offending and be heard without turning a deaf ear to other people’s arguments. In the presence of such respect and kindness towards otherness, it becomes possible to exchange information, perspectives and reasonings as a function that enriches and empowers everyone present. The community, every community, grows stronger through conditions of acceptance. And of course, the opposite is also true: when facing lack of acceptance, individuals can become more stubborn, stepping up their will to persevere.

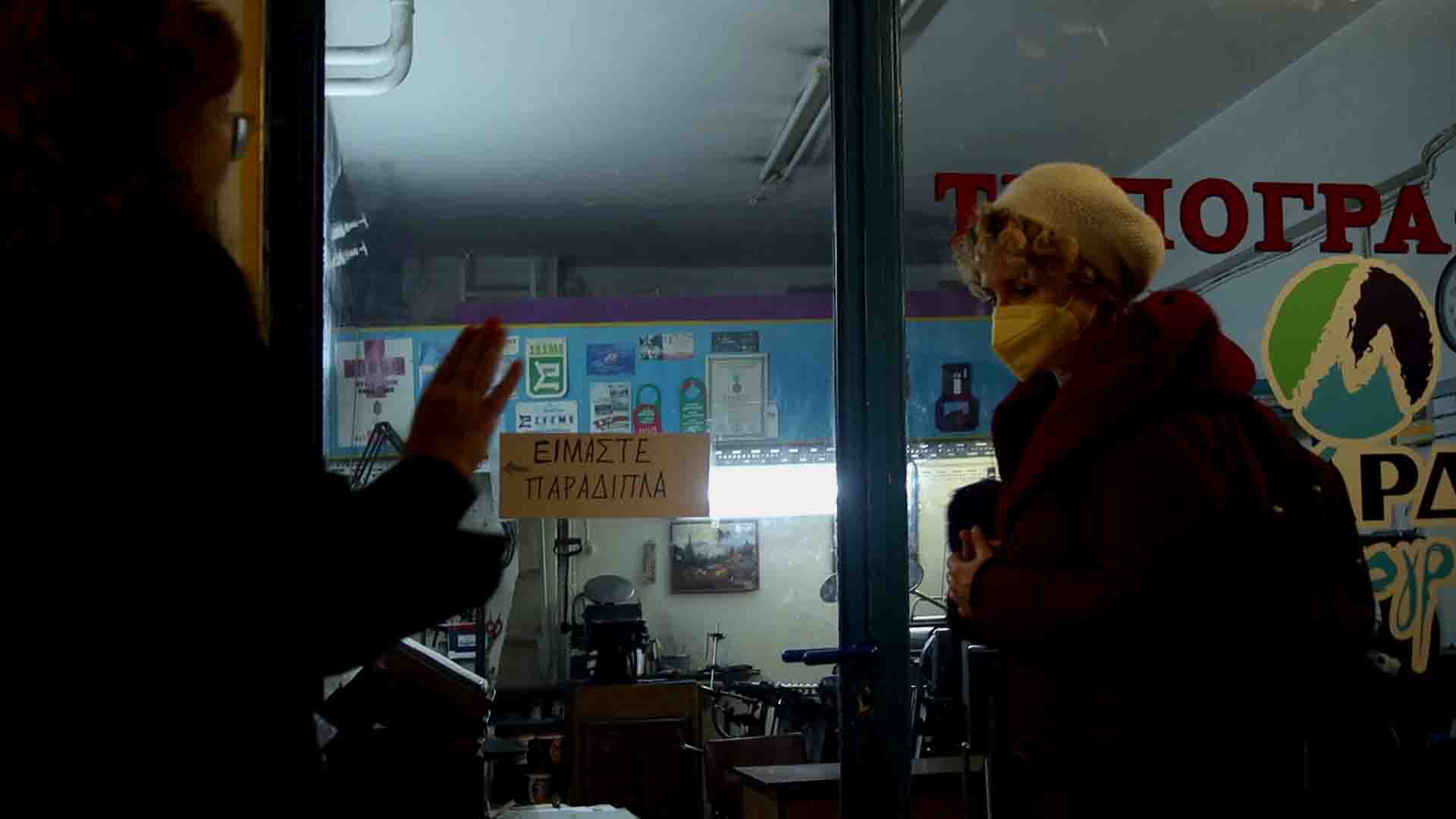

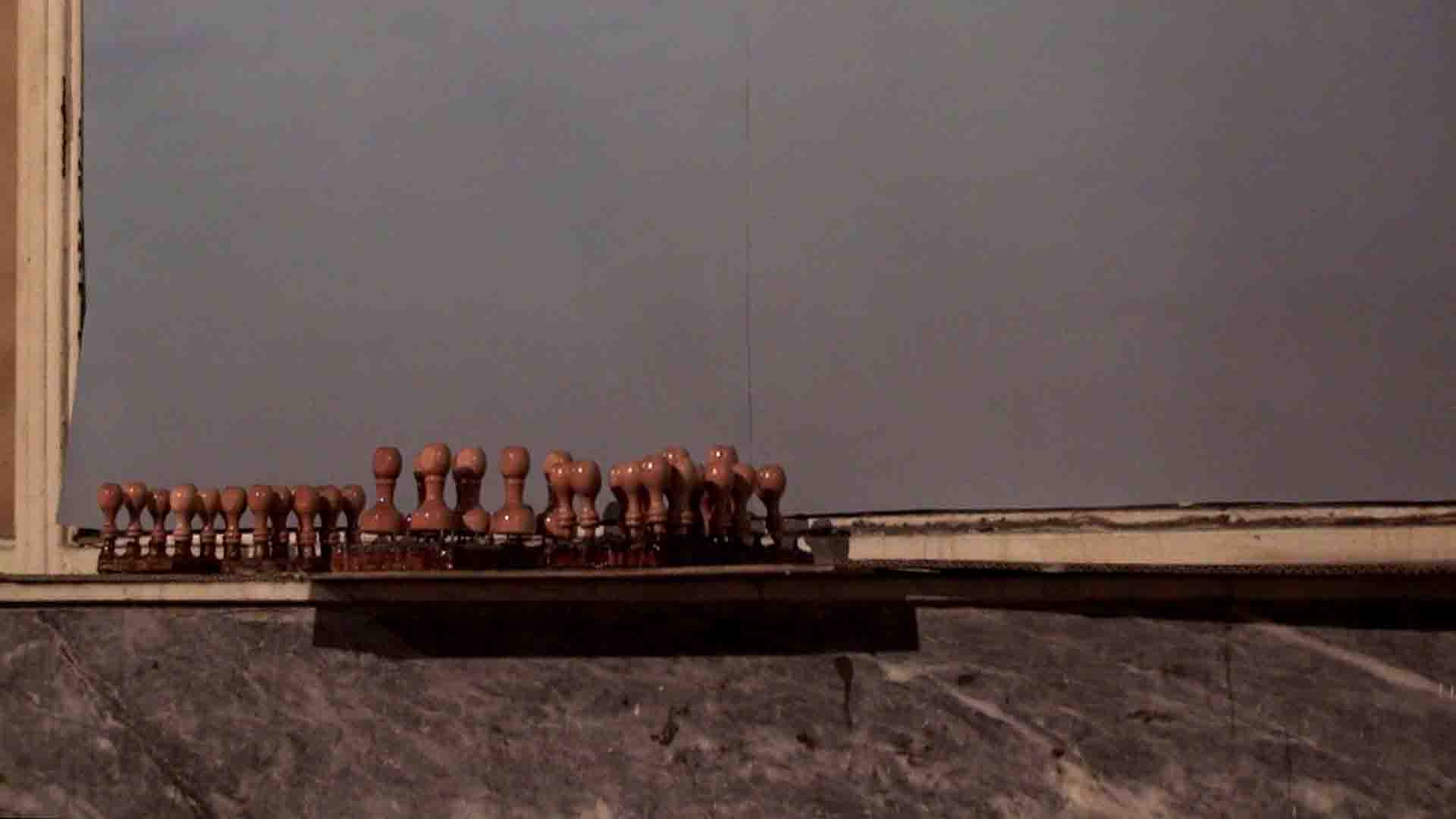

At the entrance of the gallery there is a stamp shop with a father and a son working in it. A few meters further, again a stamp shop, again run by a father and a son and actually with the exact same sign on the front. It is not a coincidence, quite the opposite: Two brothers, who had worked together in one of the two shops for years, decided to pass the business on to their children. But how exactly? Good question. The frustration, conflicts and bitterness that they describe to me for days explain why today they spend their lives in the same block without speaking. The tension from the most ancient drama in the history of dramas is forgotten when we go down to the basement and the father shows me how he cuts, curves, paints and engraves stamps from single pieces of wood. “I am an engraver, really; I used to make medals, plaques…” he tells me.

The fast-moving craftsman comes in at 5am to varnish, so that the space isn’t smelly anymore when the rest of the stores open. If one was to do an olfactory mapping of the space, the basement would be the place here the heavier scents prevail. The smell of the varnish is mixed with that of printing ink, mostly covering the fainter sour smell of gasoline and oil coming from the parked motorbikes at the lowest point of the gallery, the bottom of its belly one might say, where, should a really heavy rain fall, it would flood first. Going upstairs, the smells become aromas, and the whiff of coffee from the canteen covers pretty much every other odor. Even higher, every smell is washed away by the abundant air. An opening in the middle of the ground floor atrium brings fresh air to the bottom of the gallery, at its deepest and darkest spots, where the stamp maker’s workshop is.

The fast-moving small-frame craftsman comes in at 5 in the morning to varnish, so that the space isn’t smelly anymore when the rest of the stores open. If one was to do an olfactory mapping of the space, the basement would be the place with the heavier scents. The smell of the varnish is mixed with that of printing ink, mostly covering the fainter sour smell of gasoline and oil coming from the parked motorbikes at the lowest point of the gallery, the bottom of its belly one might say, where if there was a really heavy rain it would flood first. Going upstairs, the smells become aromas, and the whiff of coffee from the canteen prevails. Even higher, every smell is washed away by the abundant air. A hole in the middle of the ground floor atrium brings some of the fresh air to the bottom of the gallery, at its deepest and darkest spots, where the stamp maker’s workshop is.

When the craftman has prepared the stamp’s wooden handles, he dips them in a box full of varnish, fastens them to the edges of the box to drain and then spreads them to dry on the windowsill of the closed restaurant next door. In its glory, this restaurant was always full, and among its patrons were many famous personalities of the arts, such as the actress and former Minister of Culture Melina Mercouri who dined there on a daily basis. When the Armenian man who owned the restaurant died, the place was bought by someone else who ran it as an eatery for years until it was eventually abandoned. Many shops are closed in the gallery and of the open ones, most were passed from parent to child. On the ground floor there’s a locksmith whose elderly father, a former locksmith himself, still passes by every now and then. The current locksmith’s memories of the gallery are as long as his life, and the same is true for Costas, the son of the engraver in the shop next door and the typist’s daughter who’s working on her laptop directly opposite them.

“I educated my girl,” says the mother, who has been renting a space and working here as a typist since the 1970s. “If you write something about her, don’t just call her a typist, say she’s a translator”, she emphasizes, speaking for her daughter, who nods and smiles next to her. The daughter now translates into four languages while her office takes up work in all the languages of the European Union. Both women refer to God with great frequency during our conversation. When I mention that I am not a believer, they appear shocked and immediately ask me if I am Greek. I answer that I am but all people are different, just like the flowers in a garden can’t be all the same. We exchange many metaphors and similes, and soon jointly agree that kindness is what matters most in a person. They ask me if what I make will appear on TV, I explain that it won’t, I will only listen to as many stories as they want to share with me, which I will later tell to others: everything will be conveyed in words. Their disappointment is obvious, perhaps because they cannot imagine such a text to have a large audience. (Yet you, dear reader who’s still here, subvert these expectations.)

I am told that there were many typists here in the past, at least five or six offices, serving the needs of the surrounding ministries and agencies such as the Urban Planning Bureau that was housed on the 8th floor, Press Associations and Clubs, notaries and law firms that are still operating in the building today. There were also many tailoring shops, fully busy back when people used to get bespoke clothing, and a number of related shops: ironing services, shops selling spare parts for sewing machines whose costumers were the tailors, and a shop where the typists would bring their machines for repair.

I realized that people and their work were not only connected to the city but also to each other, forming a kind of micro-economy, like a hive or a village.

“We used to support each other,” three different people told me at different moments, trying to speak to me about a change in perspective or a shift in the prevailing morality that I’m not sure I really understand. Perhaps this change is better understood by those who are not involved in transactions, and are observing more than they are active, such as, say, the doorkeeper who also serves as a guard and a front desk person. Instead of “Doorkeeper” the small sign on the glass in front of his office reads “Vassilis”. Son of a former janitor who is now retired, he loves old trains and has filled his booth with photos and postcards of last century wagons. He even has a youtube channel with his own footage of various old trains, and if you look closely it seems a bit like he has transformed his tiny space, that is covered in dark wood and has a large glass opening in the front, into a train driver’s canopy, where he remains motionless but the world around him moves dizzyingly through time. He is usually reading something, while over his head a model of an old plane is hanging from a piece of fishing line. The two square meters where he earns his living lie in a small parenthesis between the two elevators and reality.

In the basement, where the heaviest machines would always go, the most noisy operations take place. If one were to make an audio mapping of the space, s/he would observe that the volume of sounds coming out of the gallery decreases as we move up, until the almost silent offices at the top floors of the gallery’s building. Galleries used to host groups of certain professions and in this one, although it did house many kinds of workshops, you’d definitely find printers. Today, of the 11 printing shops that once existed here, only one is still in operation, where an old German Heidelberg machine still breathes rhythmically, printing, cutting, punching cards for wedding invitations or other special occasions. “The Germans did everything very well, both the good and the bad things,” says the machine’s operator.

“Printers were dying young and no one knew why,” Mr. Nikos tells me next to the machine that looks like it’s dancing. It took years to discover the poisonous effect of the metal from which the movable metal type characters were made, which the printers handled all day, breathing in the dust that was produced as the machines kept pressing them. Since the mid-1980s, when he took over his uncle’s shop there, he has seen the gallery change a lot. Nevertheless, the room where his analogue printing machine is pounding has not changed at all. I ask him about the horseshoe I see hanging on his wall, if he has put it there as a charm. “Nah, I didn’t, it was there when I came,” he explains. I ask him about the two landscape paintings on the back wall, placed symmetrically on either side of a long fluorescent lamp. He has no idea, he has never really paid attention to them. He found himself in this job to make a living and for no other reason. What did he dream of becoming? “A footballer or a singer, like most kids,” he says. The rhythmic sound of the Heidelberg next to us sounds like the groaning of a train and Mr. Nikos says this sound makes him sleepy. I ask what his favorite spot in the gallery is.

– I don’t have a favorite spot. I was never attached to this place, what is there to love here? If you ask me how I feel about people, about living organisms, then I can answer.

– Actually, there are many pots with plants and trees on this level, who takes care of them?

– I do.

The next day I brought for him a small plant I had at home. I didn’t find him in his shop so I left it at his door. As I realized later, he noticed it and had moved it closer to the light. The next day, during the Emotional Tour, many people came and watched with great interest how he was working. None of them had ever seen a functioning Heidelberg machine. Among other things, they asked him what he likes about this job. “I like it when something is difficult,” he replies. He took a thick black piece of paper with tiny thickly embossed gold letters on it off his shelves. As I looked at it, I couldn’t imagine how it was possible to make something like this using analog mechanical means and not watch it get smudged to a single glorious golden stain on the cardboard. “This is very difficult and I like to make it,” says Mr. Nikos, smiling.

Next door, Mr. George described to me how, two years ago, someone, probably a child, managed to sneak in the store by slipping between the iron bars of the shop window and steal all they could from inside. His security camera recorded the top of their little head coming and going in the store, filling their pockets with mobile phones. Mr. George has been here for over two decades and over these years the whole economy has changed, he said, in his case undoubtably. 20 years ago he had two shops in the suburbs that worked wholesale with several employees, today he keeps the retail shop in the gallery by himself.

In the basement there used to be many different kinds of workshops, a goldsmith’s shop, shops that repaired televisions, refrigerators and other appliances, and someone who fixed loudspeakers. The bulkiest and heaviest machines went in here. Today it has a few stores with electronics, but mainly digital printing places, which is what the printing press shops were transformed into. Inside the largest of them, a part of the ancient wall of Athens stands out among the printers. It must be over one meter high and the people coming and going next to it use it as a table, for their folders, cigarettes and landline phone. It looks pretty surreal. If one leaves the gallery, walks on Aristides street and enters the next gallery on that street, in its basements, he will find the ancient walls again. While the buildings above them are divided into distinct units, deep below, the wall continues its single ancient course.

This sense of the past inside the present is pervasive in the gallery, and the exhibition set up by Maria Karathanou and Angelos Christofilopoulos adds tension to it. The images they bring into this gallery -as-palimpsest are also the result of a personal fermentation with the space. Even at a first walk in the facility it becomes clear that this is a response in terms of a sensual sensitivity, and not the result of the application of some strict concept designed in an office elsewhere. Just as time unfolds from the inside out, blooming in a way that no one can predict, so the gesture of this photographic installation arises from a dialogue with the uniqueness of the space. Photos of Athens from the period of the first lockdown in 2020, of the economic crisis of the previous decade, of the first day of the Greek version of the indignantos movement, are intertwined with images of nature, the countryside, or other cities. The place itself is a vessel of memory, residents and visitors have memories, and artists share their memories as well. By listening to each other’s memories, we broaden, expand, and connect better to what is woven out of time, space, and our understanding of it: the world.

Present, past and the future we imagine, are all interconnected.

Triangular wooden ashtrays, once filled with sand to extinguish cigarettes safely, can still be found on the floor outside the elevators of the eight-story building, although smoking has been banned indoors for years. The square pieces of carpet under each ashtray also remain, although the cleaning lady who had added them “for beauty” has not worked here for years. The only reason these absurd traces are still around – empty ashtrays with a flammable carpet underneath – is that someone remembers who had put them there. The traces are cumulative and are maintained either through need or tenderness for the people whose memory they bring back. The pulse of the capital, which has been beating steadily in the gallery for 70 years, has retained a stock of the iconography connected to a lost world. The interest lies precisely in the mixing and coexistence of the many different systems of thought, ethics, aesthetics, habits and aspects of locality, in an organic, amalgamated, unique way.

For me, what is interesting in the photographic installation of Karathanou – Christofilopoulos is also here: the adoption of this pattern of discourse, in a modus operandi that prioritizes organicity over a grand idea. And if my contribution made any sense to those who attended the Emotional Guide, it must have been for the exact same reason. No tour was the same as another, because they were all adorned with conversations with people from the gallery, who kept moving unpredictably, coming and going. The man we met with the 1pm group had left at 3pm and the slow Saturday chat he had with us was not possible in the commotion of a Tuesday. Each Emotional Guide was different but that did not obstruct from the goal they all shared:

To open up doors, so that they would remain open and one could return later to a place s/he understands, among people who do not feel like strangers any more.

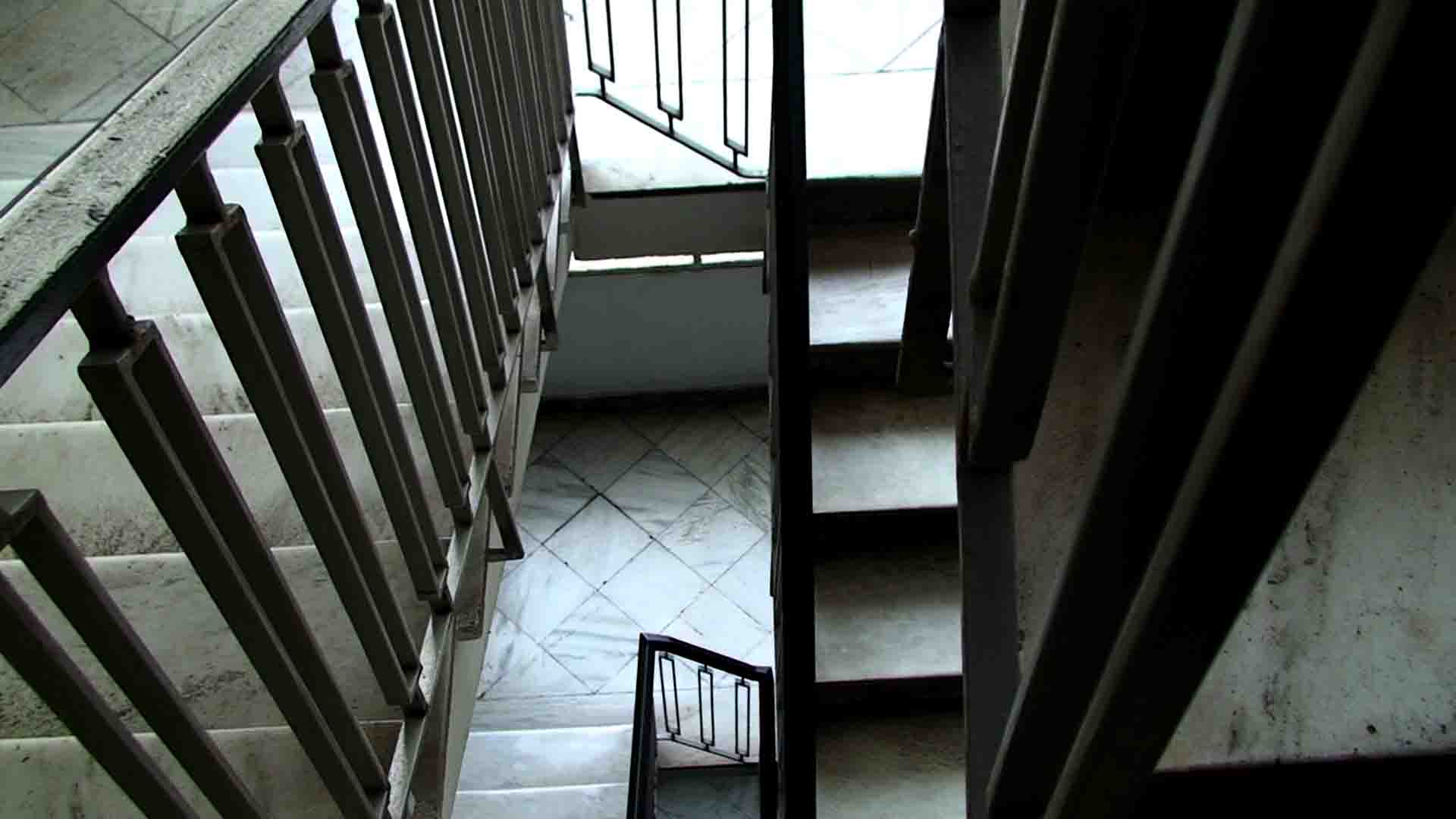

The open-air patio with the two large openings, which bring light to the bottom of the gallery complex, is surrounded by an 8-storey building and a soft lambda-shaped 2-storey building across from it. On the taller building there are many residents who tried to cut-out their spaces aesthetically, that is mentally, from the rest of the building, with various internal decoration interventions, while the lambda building remains homogeneous, at least externally. Standing on the courtyard of the ground floor you can see Mrs. Nena’ bags, the shop with the handmade jewelry that Mrs. Maria makes from real flowers, the entrance of a digital printing storage space, a shop window covered with newspapers where the knives of workers in the fish market are sharpened and often smells like fish, as well as several closed doors that remain enigmatic.

Outside of a door I read “typing services” but I can clearly hear a nailing sound. When someone comes out I wonder if I can ask him a question, he says yes, and I continue: what are these sounds I am hearing, is it really nailing? “Those were two questions,” he says seriously. I get confused for a second and then we both laugh. This was a kind of humor that I hadn’t encountered for at least 20 years. I learn that in the old typing services shop, canvases are nailed on crates so that they can be sold to the shop across the street, where painters buy their materials. This little dialogue was not the only moment when some way of thinking, speech pattern, expression, or sense of humor that I hadn’t seen for years, appeared in front of me in the gallery.

I had to repeat many times that I am married, since I was asked so many times that in the end I was saying it by myself. Even so, two different people, well over 70, methodically removed from my coat any trace of lint they could or could not see, touching me repeatedly. Others told me “shocking” jokes with which I neither laughed nor blushed since I explained that I find it quite normal for a couple to make love and in various ways too, earning the statement from their mouths that I am “very emancipated.” Apart from my marriage, that I had no way of proving without a wedding ring, and my atheism, I also had to explain where I am originally from and why I don’t have children, all conversations that I haven’t had for years. Is this really an old way of connecting to others that has survived here, in this little pocket in time and space, or is it that every time a micro-community is formed in a certain space the codes that have been mostly abandoned in the city are revived?

The first and second floors of the lambda building have communal toilets in the middle, and small spaces lined up on either side that are now used for classes, holistic treatments, services, or workshops for craftsmen or artists, according to the building’s originally intended function. Some utility bills are piling up outside a small window, next to it a door opens and a little dog comes out, very excited to see me, the dog runs to bring me a ball that I throw at him again and again. From day to day the balconies here are hosting more flower pots. Where there is light, life is welcome and the gallery has natural light on all of its five levels. Last time I was there I saw two strawberries growing under the fresh green leaves of a newly planted life.

The paths one can follow inside the gallery can be walked in many variations like a choreography would. In terms of topography, the gallery always takes you back to Aristides street, there is no way to use it to travel across the block. Many of the people I spoke to had changed their location within the gallery over the years. The locksmith moved across from his old shop because the new one was bigger. The stamp maker went from the basement to a shop on the street to be more visible, the tailor went up a floor to gain an extra room, etc. Their movement through space over the years could be illustrated choreographically like the movements of small spheres on a pinball machine. However, as I listened to everyone’s hands working, to their mouths speaking, their feet moving, I began to perceive the space primarily as a field for relationships.

If the first act of the constant choreography unfolding in the gallery were about people’s movement from space to space, the second act would expand on the relationship between them: how the French teacher buys a handmade necklace from a lady on the ground floor, the waiter of the coffee shop repairs his key with the help of the engraver and the visual artist on the first floor buys a cheesepie from the canteen before returning to his workshop. In this act, passers-by like us can fit in too, thus the flyers for Sisyphus project were printed in the basement, every day we had our lunch at the canteen, and I brought one of my coats that needed lining for Mr. Thanasis to repair. The sign with his name on the door is now accompanied by one more, that was a gift from friends after his official retirement. It is placed under his name and reads: ” Haute couture and gastronomy friends Club” since the shop now functions more as a meeting and hangout place. Almost everyone who comes in and out of there is now retired and maybe they have something that needs sewing, maybe they don’t; store hours are still observed though, even if during them they watch a little TV, or spread a plastic sheet on the cutting board at noon to share some olives, onion bulbs and raki.

My coat was taken carefully out of the bag, studied, examined: yes it can be lined, it was concluded. How much will it cost? “As much as you can afford, as much as you want.” The next time I went to the shop, the whole haute couture committee was there. They decided exactly how the job would be done. How much will it cost? I asked again. This time I heard a three-digit number. I hadn’t expected it to be so expensive so I asked if I could pay in installments. No problem, they told me, I could pay in as many installments as I wanted. A little later, without me asking again, the price fell in half. I laughed at the relationship that they seemed to have with money. I felt as if they were not working for money, but to stay alive, to keep their spot within what they recognize as themselves, but payment is necessary in order to keep the game going. Like in a monopoly game, where money is not exactly money, but we are definitely there exchanging it.

On the other floors of the 8-storey Anatoli building, one can observe a wide range of interventions to the space that differentiate parts of it from the rest. Some corridor walls have been dressed in dark wood while doors have been replaced with old style safety ones. Somehow it feels like being in Arizona during the ’70s. On another floor, black glossy tiles are pasted all over the left side of the corridor, on top of the blonde mosaic, while golden knobs with embossed lion heads adorn the doors. The eerie reflection of fluorescent lamps on the shiny tiles creates a strange darkness during the day and an imposing atmosphere to the point of fear. On many floors, entire corridors are either illuminated in a distinctly different way, with white or yellow light, blocked by iron railings as if they were courtyards, or even hidden behind false wooden walls.

On the lower floor, outside a state mental health service office, a hand-written sign announces that no one should smoke in the hallways. It is the only floor where the triangular ashtrays are missing and the window of this floor is the only one with a sill always full of cigarette butts. A sticker at the lower part on the service door dictates: “Do not kick the door.” If one manages to refrain from judging these interventions that have been carried out over a period of several decades, and tries to decide later whether it is more legitimate for things to remain unchanged over time or not, can see a source of information in every little detail. The use, the abuse, the problems of the building but also the fantasies of the different owners for the spaces they were using, are reflected in their modulations. Every tile that covers a piece of mosaic, every security camera, every aesthetic or functional tampering describes the relationship of people to the space they had access to. Every attempt to solve a problem leaves a trace and so does the intention to become autonomous and enjoy a private fantasy context, an ideal transformation into some other place.

Apart from everyone’s relationship to the space, though, to others as part of a mobility network within the gallery, or to the wider city as it manifests through the stories of how everyone ended up there, the relationship to memory itself is dominant: an excavational relationship concerning their own personal memories, and now mine too since they were narrated to me, and now yours too, since you’ve been reading up to here. People remember and are remembered here. Many of those I spoke to opened up for me not only the folds of their past but also the episodes of their present adventures, creating new memories, like the secretary of the press association whom I met at the cafe and we analyzed together the pluses and minuses of vaccination in relation to potential allergic reactions. The past does not exist somewhere waiting for us to recall it, but is made every second and is being distributed to all present parties like hot bread.

Entering the gallery, listening and observing, I did not try to record my empirical data but to do what a person arriving somewhere for the first time usually does: to understand where I am. When I first entered the Anatoli gallery I saw only dust, closed doors, walls, railings. By discussing, listening, touching, working with my hands and ears, everything, every door and corner, began to gain depth, open up, unfold, as it happens when you get to know a person: on the first meeting you say your names and the other person is just one face in the crowd. As you get to know each other and become connected, one begins to transfer her/his experience to the other, to exchange herself with his self as one of the communicating vessels that make up what we call social space. By understanding, you relate, and as long as you relate you understand something new.

The last relationship I want to mention is that between light and shadow. Traditionally, galleries have always housed stamp shops, bookstores, and printing houses, because the guaranteed shade eliminated the threat of the destruction of paper and paint by the sun. And indeed, close to the two entrances and in the shadiest parts of the gallery there is a shop with stamps, coins and banknotes. Entering one of the two, I met the son of the man who had first opened it. His very first memories are collected in this piece of architecture. “You’ve been coming here since you can remember, what did the gallery look like when you were a child?” “Chaotic…” he tells me. This store has moved from its original position too, in order to gain more space, always away from direct sunlight. The whole gallery could be mapped as a field of alternating lighting conditions, which grows more intense as you walk up the two buildings’ floors, up until you get to the roof of the 8-storey one, where I’ve been told a little garden is kept, with trees and a vegetable garden that I never saw, belonging to an occupant that I didn’t manage to meet. The brightest spot here remained for me the most obscured: only what we have known is illuminated.

There were people who opened their warehouses to us and cried. Like Mrs. Dimitra, who brought their parents’ honorary plaques from home to show them to us and tell us all about what remarkable, good and hardworking people had been those who first started a business in the gallery. However, most did not cry. Neither out of emotional overflow nor out of melancholy. Most of the people I spoke to in the Anatoli gallery had their psychic sleeves rolled up and their hands full with the work of adapting to a world that never ceases to transform, with a life full of obstacles where they manage to remain standing, active, feisty. The little room opposite the doorman’s booth belongs to a customs company that might operate from a tiny space today, for years though occupied the entire first floor. That floor has now been purchased to be converted into Airbnb apartments and the customs company has been squeezed into 3 square meters, but it has not been closed down, it is still operating. This, like so many others in the gallery, is a story of survival and overcoming adversity.

A few meters away from the shop with the stamps, every time I meet him, Costas reveals to me a little more information about how great a victory it is that his company has survived. When they started from the beginning again, he had just completed a big job, tens of thousands of euros worth. But even though he spent many sleepless nights in order to deliver it, he never got a dime because his payment money was frozen due to a legal complication. Soon thereafter, he was lucky enough to take on another really big job, which he also did not get paid for tough, since the client went bankrupt. Nevertheless, he survived. Narrating this incredible achievement, he heals from the trauma that he had to go through. What’s more, when he thinks about what he went through, he is reassured that he is no longer afraid of anything.

Hands heal with actions and ears gets healed as they listen.

Although the meaning of memory is to hold some things from the chaotic river of time, at the same time there’s something timeless about its function. Memory is present at all times in each one of us, whole, pulsating, active, ready to emerge at the first opportunity. As it is possible in a dream to watch our mother meet a French chef, a 19th century general and some version of our future self, here too, Mrs. Nena’s grandmother’s machine, the students drinking their coffee on the patio, Mr. Thanasis taking a nap next to the electric heater, the voices of the former owner of the coffee shop and former doorman who come most mornings to check on Mr. Thanasis, Mr. Vassilis’s trains pinned on the bulletin board, the ancient wall that is continued from gallery to gallery, the smell of the varnish, the banana tree that lost its leaves from this year’s snow, form a space. An internal space that is felt by the hands and heard by the ears, a space that is magical and multi-dimensional, huge and timeless, inside which it is possible to relate. Everything is connected.

Oh, and one more thing I learned from Mr. George at the coffee shop: all galleries in the city center are connected: when exiting one gallery you are always in front of the entrance of another.

Evgenia Tzirtzilaki